Three Big Bugattis and a Little Peugeot

Every day at Phil Reilly & Co was something special, some days more so than others. This day was probably just another average one, though a search of the archive contains over 600 photos from that month in 2013, so it could go either way. Two of these cars were included in the first episode of “One Day in the Shop”, and in fact this image is from the same day, facing the other direction. So I’ll focus here on the two in the background, not previously mentioned.

The gray and black 1931 Bugatti Type 50 is an unusual beast, as reported by RM Sothebys prior to its recent auction:

Of the 65 cars built, only four were clothed in factory roadster coachwork penned by Jean Bugatti, and this is the sole remaining example with its original coachwork.

RM Sothebys Auction, Villa Erba 2019

The engine in this car is an evolution of the Type 51 Grand Prix motor, which itself was developed from the Type 35. The three-valve, single-cam Type 35 was improved after Bugatti adapted Miller’s twin-cam, hemispherical chamber design, a valve layout that was retained until the last Type 57. (Miller himself having copied Peugeot’s 1913 design, a link to the little green car in the lead image).

The Type 35 was the dominant Grand Prix car of its time, but nothing lasts forever. To remain competitive with the Italians and the Germans as they rapidly developed their technology, Bugatti went for the old American adage of, “There’s no replacement for displacement!”. From the 3.3 liter, twin-cam Type 51, the Type 54 went to almost 5 liters, and used a Roots-type blower with increased capacity to match. The resulting output was in the neighborhood of 300 HP, though the weight increased by a perhaps a third.

The road car type 50 variant produced a more subdued 200, which was still very impressive for 1931. Few cars other than the supercharged Duesenbergs could match that output, though the big American beast’s block and head were cast in iron and vastly outweighed the Bugatti. They also featured four valves per cylinder compared to the Bugatti’s two valve design.

This particular Type 50 was in for some relatively minor work as I recall, some brake adjusting and carburetor work. An interesting feature of the type 50 is the American-made Schebler Model S carb, which uses an air metering system that’s different from just about any other make. The closest analog I can imagine is Bosch K-Jet injection metering, where a mechanical air metering unit adjusts the mixture based on engine load. In principle, an SU carburetor’s dash pot does the same as it lifts the needle in its jet, a much less complex mechanism than the Schebler.

The Peugeot in the driveway is another odd duck. The 1953 Nardi/Peugeot 203 was one of a small run of cars commissioned by Maurice Dubois from the emerging auto performance firm Nardi. Better known today for their lovely wood rimmed steering wheels, Nardi originally built complete cars in small numbers, mostly with lightweight and small capacity foundations.

This car has a Nardi-built chassis using the engine and suspension components from a Peugeot 203, with the body built by Pietro Frua.

This car was in the shop for motor work, though my photos are incomplete and don’t reveal the whole story. The little 4 cylinder hemi head engine had been built to the hilt by someone prior, but the performance was limited by the awful intake port design of the original cylinder head. “Port” is a misnomer, because it did not have individual ports, the output of the blower dumped into one big open plenum where the intake valves could talk to one another, “Hi, neighbor, how are you doing?”.

It was also fed by a less than ideal carburetor, pictures of which are not in my files. A new manifold was machined to use a Weber side draft, with the blower intake port being enlarged to suit.

I did some disassembly work on the motor but I was mostly occupied by a series of Bugatti projects at the time, so I wasn’t privy to all of the discussions related to the Peugeot’s development. In the end, the decision was made to abandon the blower entirely for a pair of Webers, which required major head work and a custom manifold.

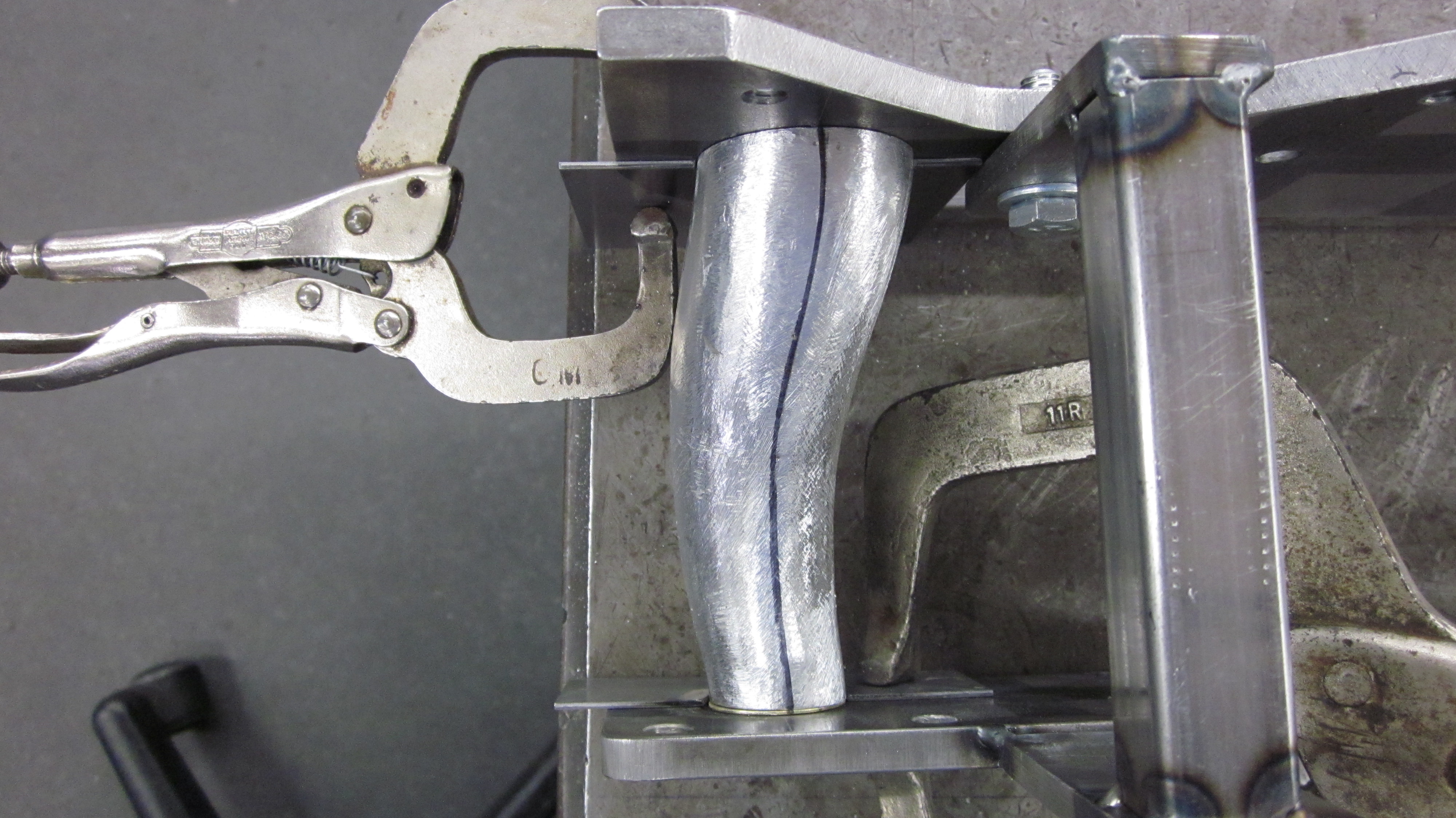

The intake ports were separated by aluminum blocks mechanically attached inside the plenum, then ports were shaped using a special epoxy material that permanently adheres to the metal. Ace fabricator Chuck Mathewson undertook the manifold… fabricated from steel sheet that was formed over solid mandrels and welded together.

In the end, the engine probably performed better than it had with the supercharger, given how great an improvement was made to the fueling control.

Back to the lead image for a moment. The two Type 57 Bugattis up top had an impromptu photo shoot out in the parking lot to compare the height of the standard chassis (red) and the ‘S’ chassis, (yellow).

The ‘Surbaisse’ model achieved its low stance by passing the rear axle through a window in the chassis rather than underneath it. This yellow and black Atalante had a little issue with its De Ram shock absorbers, such that over every undulation in the road, the axle made solid contact with the window in the frame… BANG! BANG! BANG! Pretty unsuitable for a multi-million dollar car!

The De Ram shock absorber is a remarkably complex bit of machinery. While other cars of the period, including cheaper models of Bugattis, used simple friction dampers, the De Ram is a hydraulically operated friction shock, essentially a multi-plate wet clutch. The problem with simple friction shocks is that the initial force required to move the mechanism is greater than the force required to move it once broken free. So a shock set to operate stiffly, to control high speed damping, has very high initial friction and works terribly over low speed bumps.

The De Ram can be set to operate smoothly with little friction over slow bumps and the hydraulic action dynamically adjusts the friction to increase the damping effect as the speed and size of the bump increase.

The Atalante was simply passing through our shop and it had a visit from the esteemed Bugatti specialist that had been been caring for it. He removed the rear shocks and expertly re-worked them so that the car became, once again, a sophisticated elite touring car.

I had the joy of working on three different sets of De Rams around this period and have been meaning to do a write up describing their components and some of the issues they can have. They really are something quite special. Stay tuned…

Leave a comment