I’ve worked on a pretty wide variety of cars over the years, and a consistent engineering question each of the designers faced is this: How do we keep the extremely high combustion pressures inside of the motor? If you’ve ever experienced a blown head gasket and the expense that comes with repairing it properly, you know what I’m talking about!

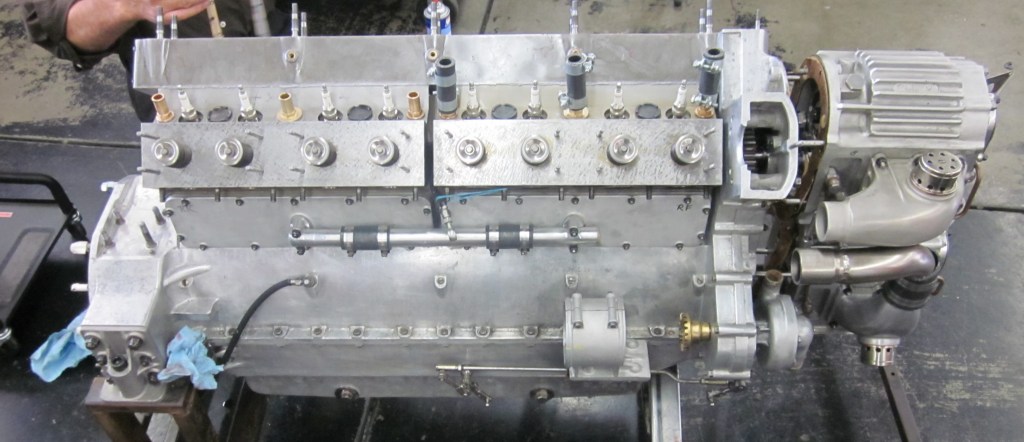

1: Monobloc Castings

Some of the oldest cars that I’ve worked on had the most effective system for keeping the pressure inside the motor, they made the cylinder block and cylinder head in one casting, also known as a monobloc. Bugatti engines from the beginning to the end had a monobloc design, and therefore are completely free from head gasket issues.

Alfa Romeo went back and forth between head gaskets and monobloc designs. The Alfa 6C 1750 Grand Sport had a separate cylinder block and cylinder head, as did the 8C 2300. But when they went to the 8C 2900, they eliminated the gasket and used a pair of monoblocs. All three motors were supercharged.

The Maserati in the featured image at the top of this page is an 8CTF Grand Prix engine with twin monoblocs for its 8 cylinders, supercharged by twin blowers mounted up front.

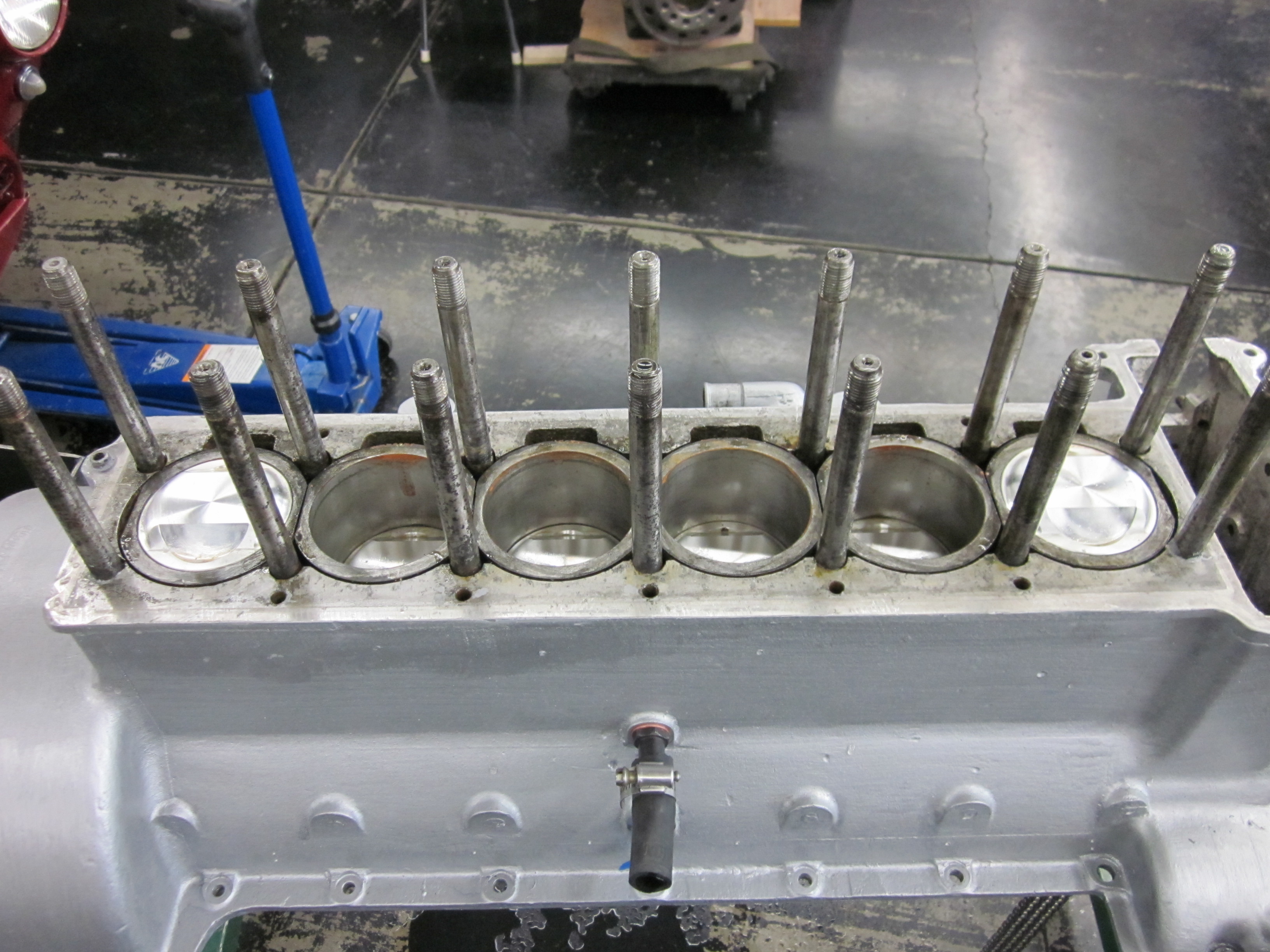

There are substantial downsides the the monobloc concept, however. One issue is that for assembly, you cannot feed the pistons in from the top, with a ring compressor to ease the rings into the cylinder. The Bugatti Type 57 image above shows the assembled monobloc being lowered onto the crankcase, slung from an overhead hoist. Each piston needs to be fed by hand into the block as it is lowered, using your fingers to compress each ring as it enters the bottom of the cylinder.

Some engines are easier than others when it comes to this task, and ring design can help or hurt. Modern 3 piece oil rings with very thin rails are difficult. Old school one-piece cast oil rings are much easier to feed into the bore. The style of taper at the bottom of the cylinder also makes a difference.

The other major downside of monobloc design is that machine work on the valve seats has to be done through the bottom of the cylinder, which limits what kind of tools can be used. Cutting valve seats in a monobloc engine is a time consuming operation, compared to using a modern Serdi machine on a conventional head. Valve assembly in the head is also complicated. Here’s a brief look at what’s involved in a Bugatti Type 57 valve job.

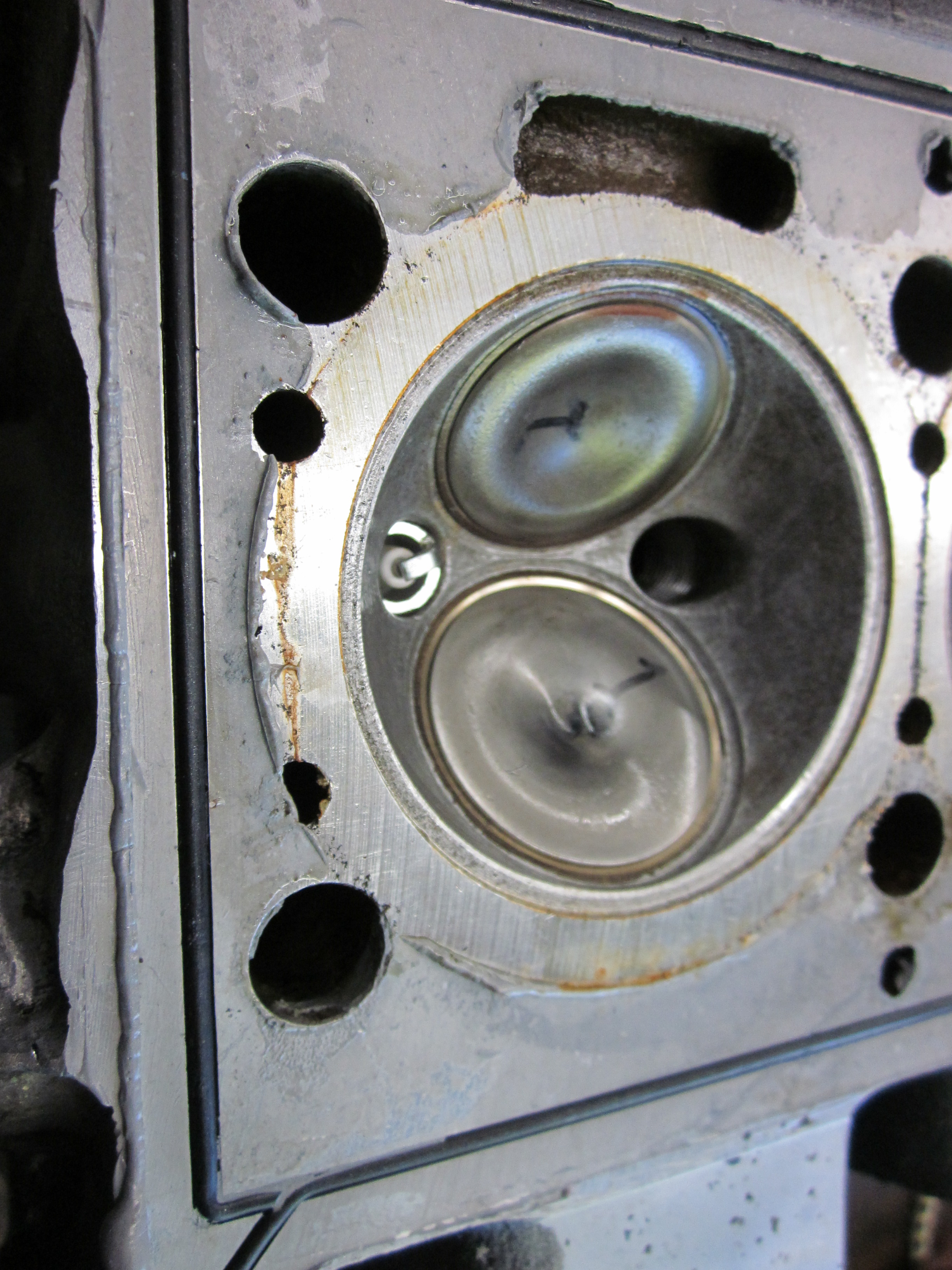

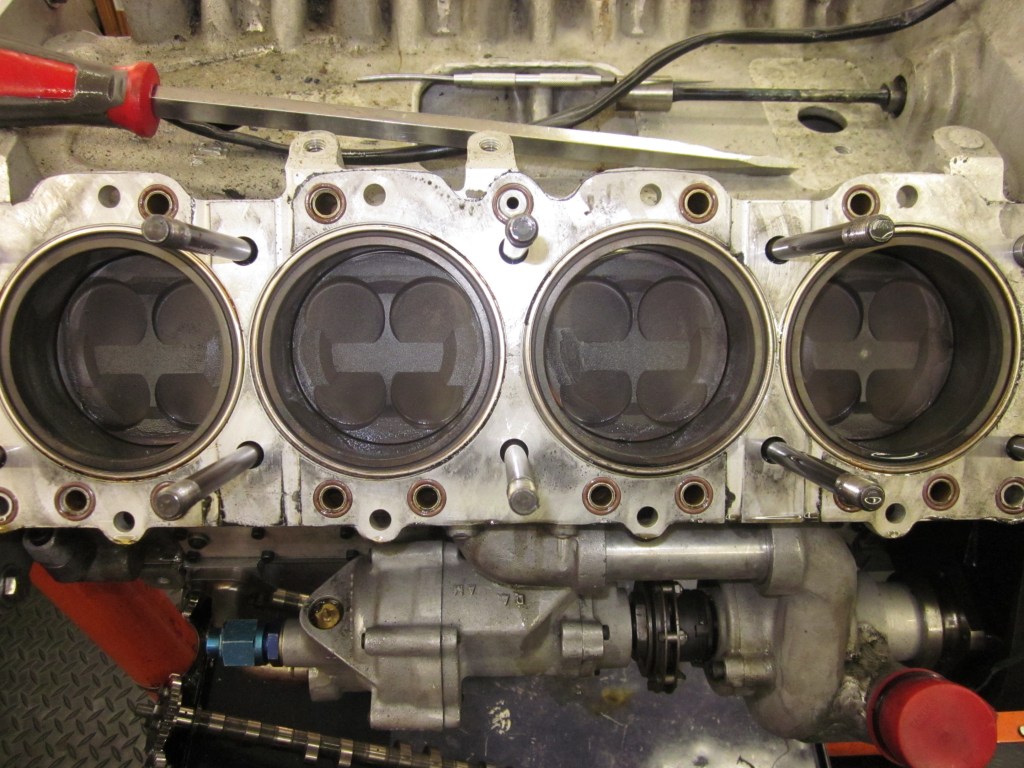

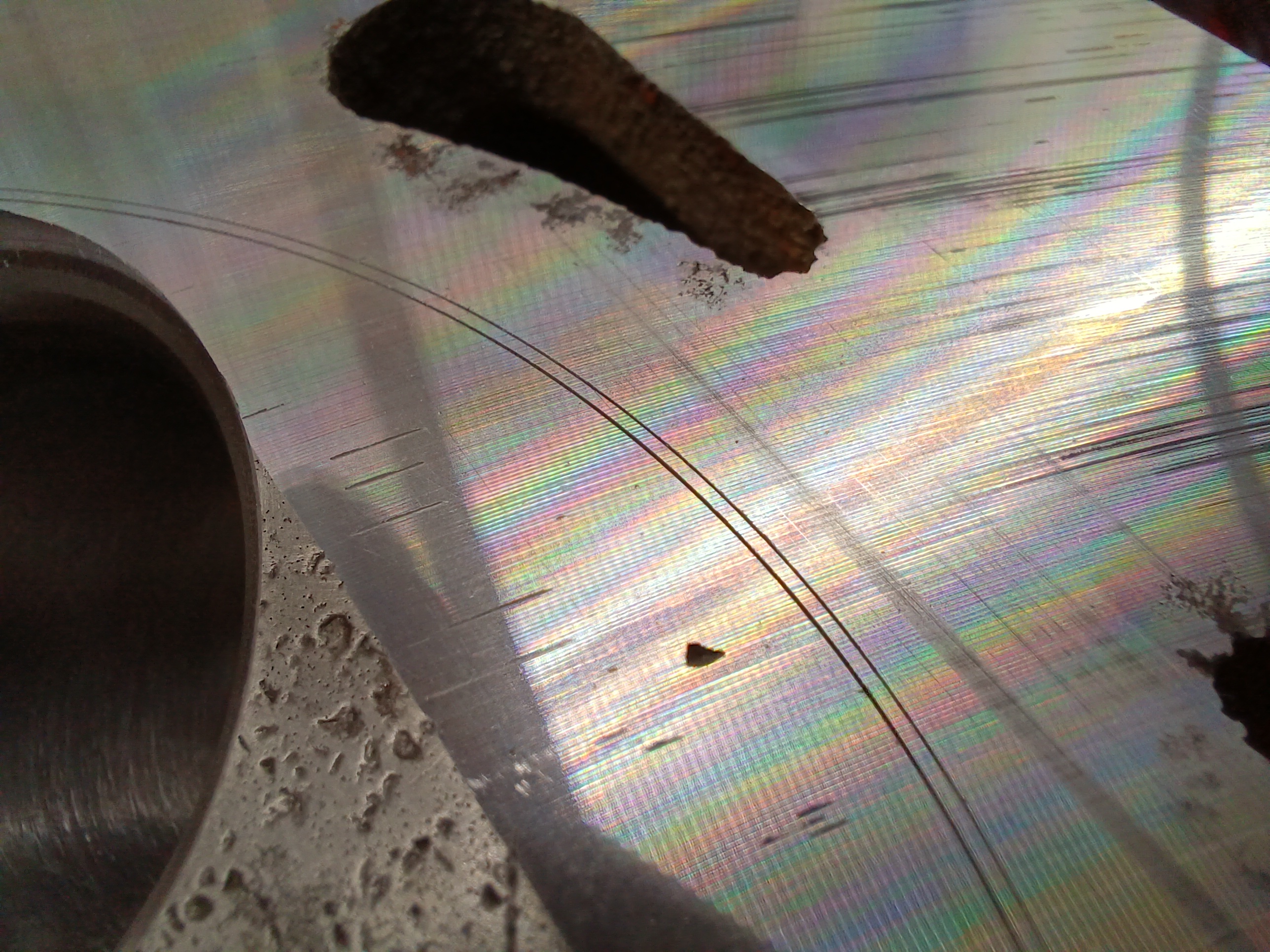

2: No Gasket – Metal on Metal

There are some engines that use separate head and block castings, but do not use a head gasket. Maserati was fond of this technique, which I encountered on the Type 61 Birdcage engines as well as the A6 series. These engines use iron cylinder liners fitted to an aluminum block, and the liner is intended to protrude about .002″ above the aluminum deck. The bottom surface of the cylinder head sits directly on the top of the iron liner, and the tension on the head studs is enough to seal the pressure in and the water out, but the mating surfaces must be perfect, and the type of machined finish matters. The liners must be perfectly the same amount above the deck… if one sinks a bit after machining, the seal has no chance. The water is sealed on the perimeter of the head with rubber o-ring material, backed up by modern RTV silicone these days.

3: Cooper Rings

Next in line of the different concepts to handle combustion pressure is the Cooper Ring. I’ve been unable to track down who invented them, though it probably was an aerospace company in the UK called Cooper (unrelated to the race car maker, Cooper). Today they are also known as Wills rings. The first mention of them I’ve been able to find was the Coventry Climax FPF, a 2.5 liter four cylinder engine that won the World Championship in 1959 and 1960 in a Cooper-Climax driven by Jack Brabham. Coventry Climax also used them in the FWMV 1.5 liter V-8 Grand Prix engine, which was developed in 1960. My experience with them is only second-hand, as I watched Phil Reilly preparing them for use on his Cosworth DFVs, the engine that dominated Grand Prix racing for a very long time.

The Cooper Ring is basically an individual head gasket; one ring surrounds each cylinder, living in a machined groove, and the ring is very slightly taller than the deck of the block. The crazy part is that they are hollow and gas pressurized, so they act as a spring that can absorb vertical motion between the deck and head. I have no idea how they are manufactured.

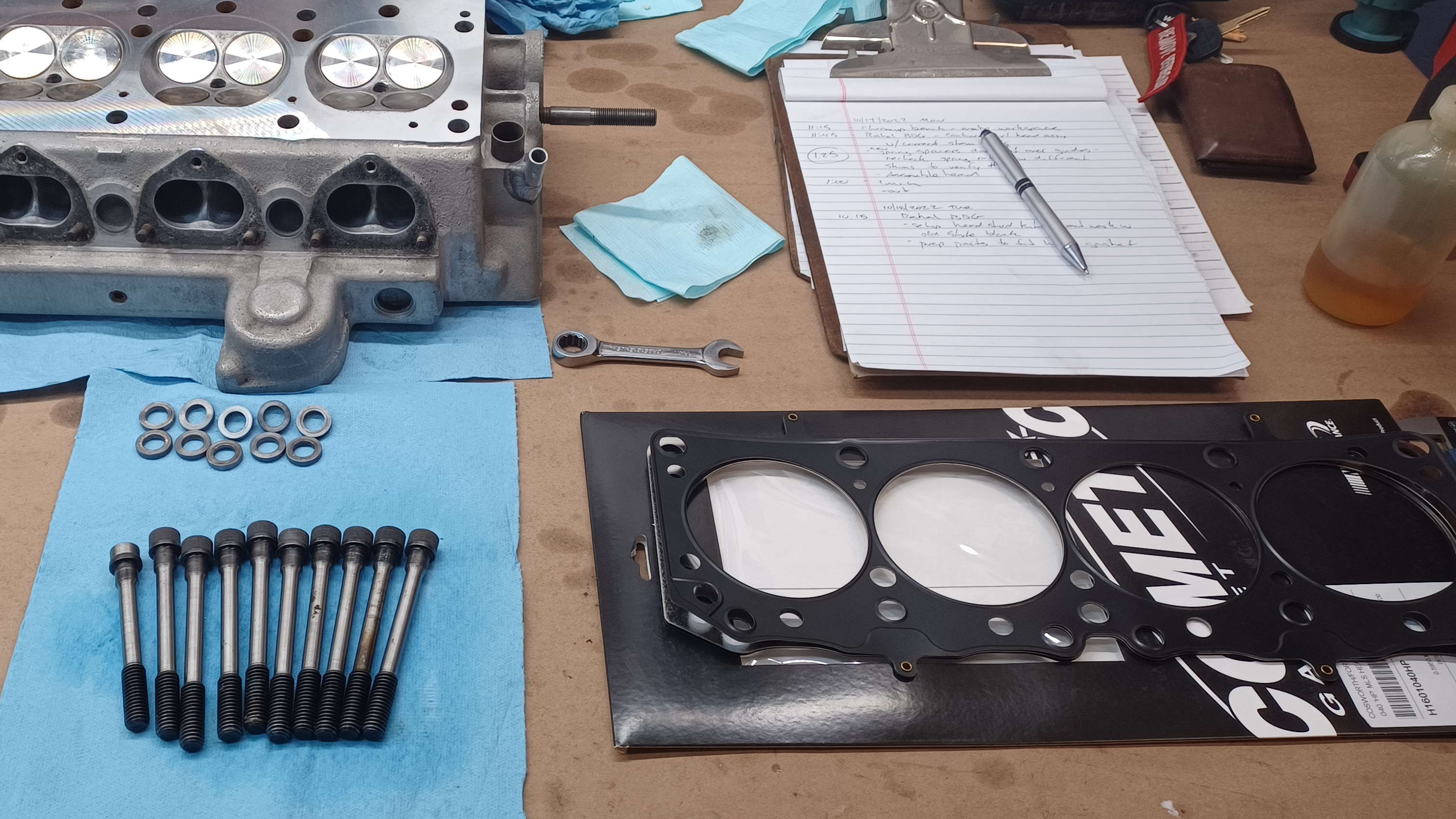

4: BMW M12 Fire Rings

While the Cooper Ring is a somewhat complex piece of engineering, I came across another level of extreme pressure sealing devices when I got involved with a BMW M12 engine program. The M12 is a 2 liter four cylinder racing engine that was used in Formula 2 initially, but was also the basis for the turbo 1500cc Formula 1 engine of the early 80s. This engine ultimately produced over 1,300 horsepower when the turbo boost was turned up to eleven for qualifying. It is safe to say that there was a lot of combustion pressure trying to escape wherever it could.

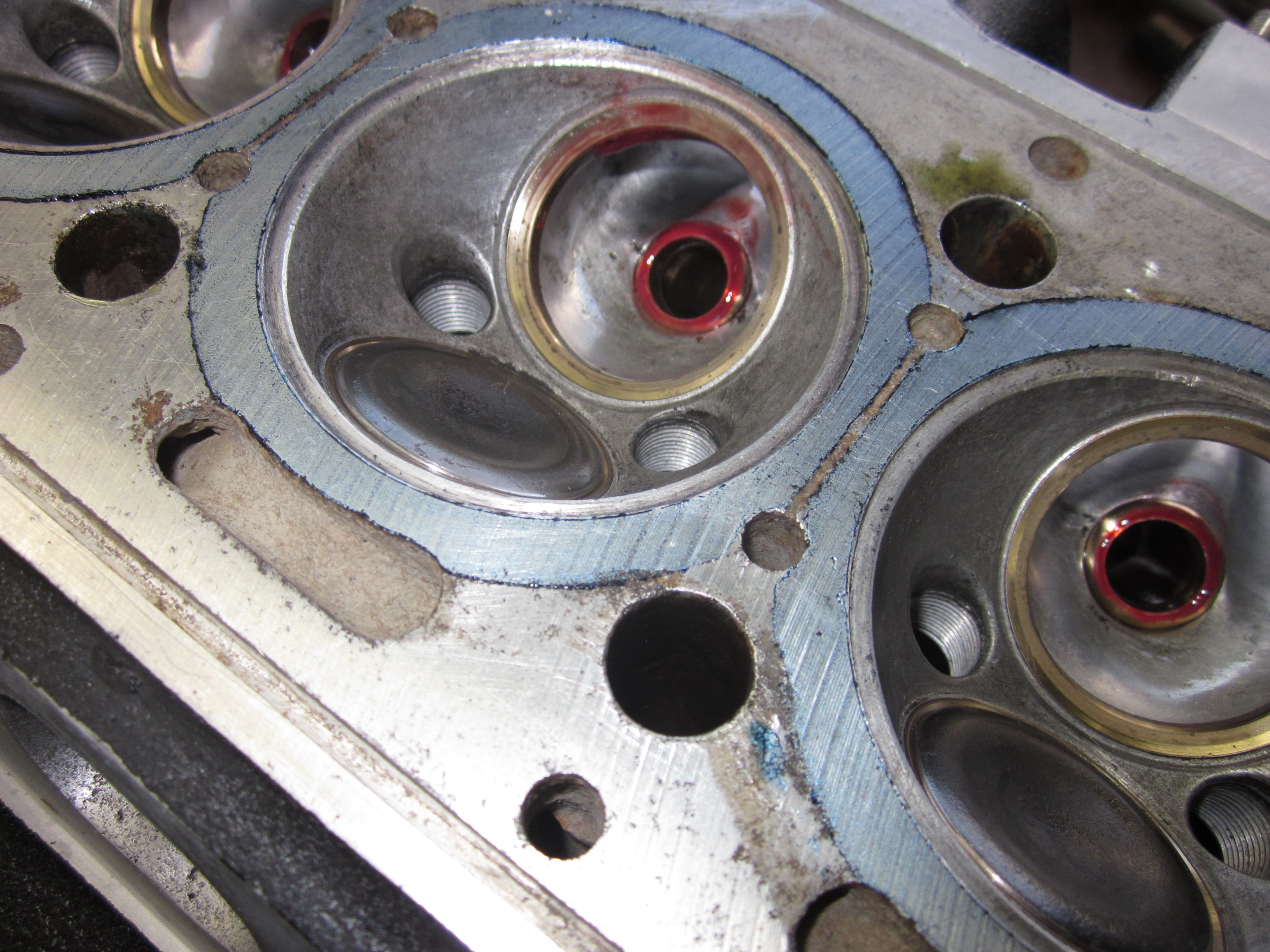

BMW developed a fire ring that lived in a shallow recess around the cylinder top that had a flat bottom and two knife edges around the top that bite into the aluminum of the cylinder head. It essentially cuts two concentric grooves in the head as the titanium head bolts are torqued to a very high number. The first image below shows a ring in its groove, prior to installing the actual head gasket. Yes, there is a traditional composite gasket as well as the fire ring. One of the many complexities of these engines is that the amount of bite that the fire ring penetrates into the head is determined by how much the composite gasket compresses. Also, the factory specified that the tolerance for the height of the fire ring was something like two ten thousandths of an inch… .0002″.

Why they went to this level for the normally aspirated F2 engines is beyond me. They produce about 300 horsepower in two liter trim, 315 with modern tricks. But the M12/13 F1 motor made FOUR TIMES that much, so the fire rings obviously had a job to do. I’m told that some of the guys running non-turbo M12s delete the rings and use a standard Cometic MLS gasket with good results.

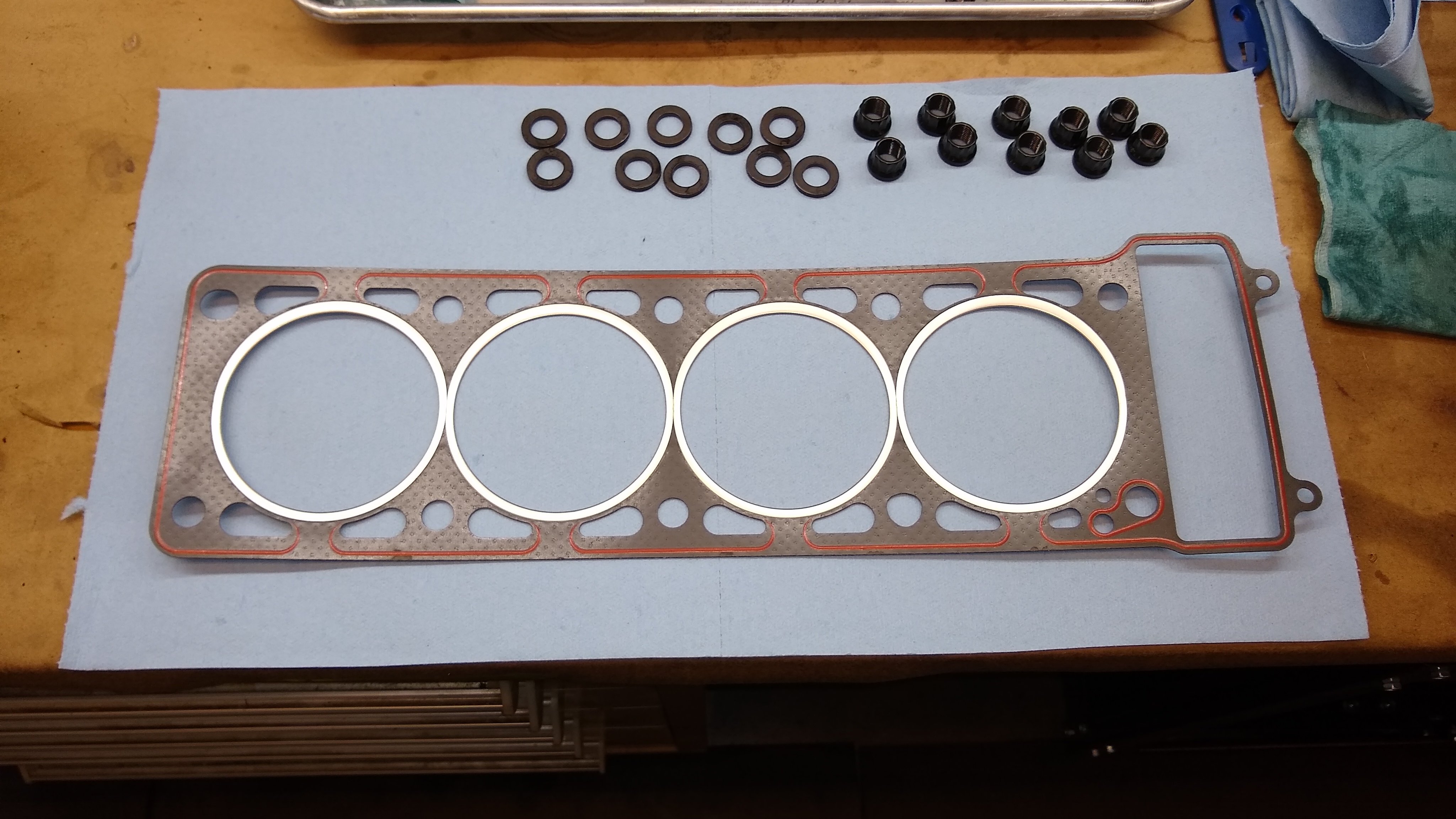

5: Solid Copper Gaskets

One other type of seal that is commonly used in vintage racing is the solid copper gasket. A sheet of annealed dead soft copper is cut to the same pattern as a conventional gasket, and is fit in a conventional manner. Being dead soft, the copper conforms to any slight variations of surface quality and can be a good option, though not always.

I was supplied with a solid copper gasket for a Talbot Lago engine project, with assurances that it worked great on the last one somebody built. I suspected there would be trouble because the piston liners were designed to sit .0025″ proud of the block deck, and I doubted a solid gasket is going to crush that much.

It did not work… so I had a conventional composite gasket made and that fixed the problem.

6: Traditional Gaskets

Conventional head gaskets do a fine job for the majority of motorsports applications. A modern version is the Multi Layer Steel gasket, a stack of several layers of stainless steel sheet with embossed areas to seal against the combustion chamber and water ports. A polymer coating helps with the sealing.

Other more conventional gaskets use high temperature fiber sheet with steel reinforcements around the chamber. Some rely on older tech that uses thin copper sheet sandwiching asbestos.

So there you have it, all the ways that I know how to keep an engine’s fire inside the motor. Let me know in the comments below if I’ve missed any or if you have any questions. Cheers!

Leave a comment