A Deep Dive into Some Pre-War French Machinery

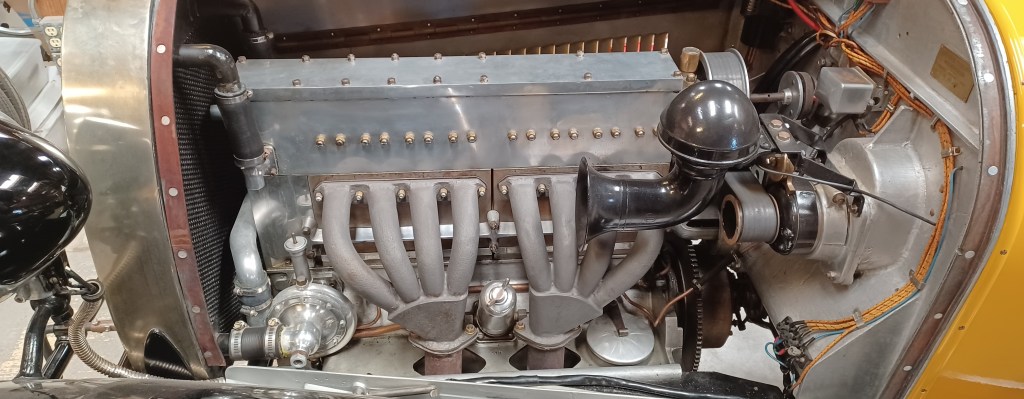

I spent a fair amount of time earlier this year getting a 1926 Bugatti Type 30 ready to do some road miles. It had been in a private collection for many years and apparently saw very little use. The new owner enjoys using his cars, so right off the bat the car needed to be able to complete a 100 mile road tour.

When a car hasn’t been used well for a long time, it can be hard to really know what you’ve got to work with. This car performed quite badly in its first test runs, though leak down tests showed the engine was basically sound. It smoked terribly and the carbs leaked fuel, with evidence of a fuel fire somewhere along the way (singed spark plug caps and extinguisher residue in the hard to clean crevices).

I started off with some basic chassis and brake work, to ensure that when it was running properly, it would turn and stop OK. Then I addressed the ignition, to make sure it was firing properly and at the right time. The plug wire set and the connections to the distributor cap had some issues, which were rectified by making a new set of wires and cleaning the terminal connections. Then the timing was checked, and I found the the manual advance control had far too much range, from way too retarded to way over-advanced. So I fabricated a bracket to limit the advance to something more reasonable, say 40°, cleaned and gapped the points, and set max advance to 45°.

While working behind the dash and checking the ignition circuit, I found some poorly spliced wires from the ignition switch, which resulted in new wires being run for the fuel pump and new terminals soldered for both ends of the coil.

Once the ignition was dialed and the pump wiring made better, it was time to look at the fuel supply. The car had a rather low-quality Mr. Gasket electric pump with a plastic body, and my gauge showed it making over 4 PSI. These cars originally had air pumps that pressurized the fuel tank to make between 1 and 3 psi, and the float valves in the carbs were selected to handle that low pressure. More pressure overwhelms the float valves and floods the carbs, so we made a few changes and ended up with 2.5 PSI with a Facet pump and a pressure regulator.

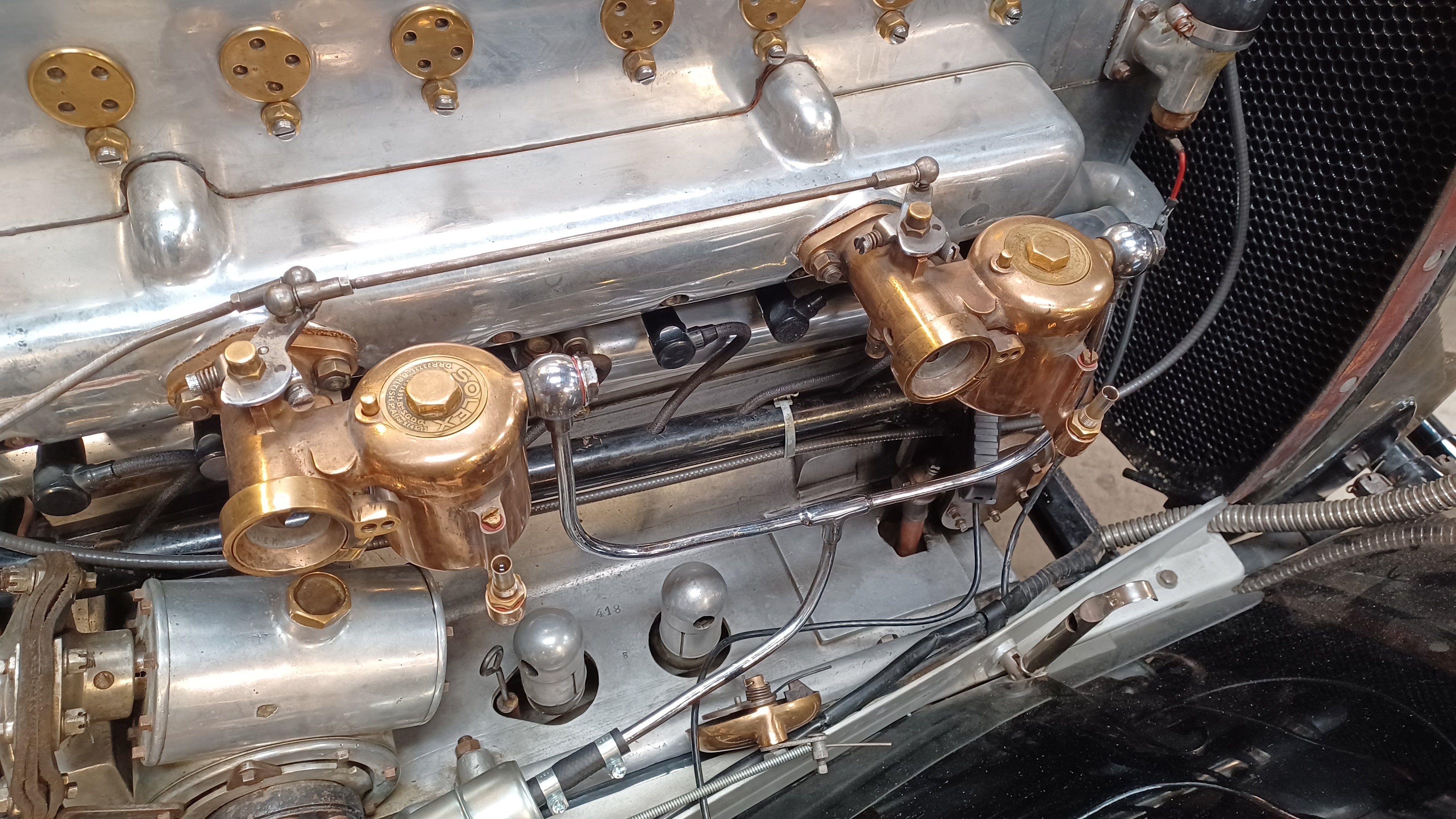

Next, I looked inside the carbs to see what we were dealing with… the nearly 100 year old Solexes were in OK shape, but had not been put together correctly. Plus, the floats had been repaired multiple times and were heavy with solder. One was still leaking and sank badly. Our ace fabricator carefully warmed the brass float until all the gasoline had evaporated out, then fixed the pinhole leak with a small dot of new solder. But both floats were still a couple of grams heavier than the design weight of 42, and the fuel level needed correcting by spacing the float valves lower in the bowl.

I measured the jets and saw that the idle circuit was on-size as stamped at .45 mm; the main jets measuring 1.25 mm instead of the 120 marking. I adjusted the float jet heights to get the fuel level 3 mm below the spillover point in the emulsion tube, 3 mm being a general rule of thumb for most carburetors. These Solexes are kind of neat in that you can easily drop the bowl with one nut, and rotate it 90°, which puts the main jet holder where you can see it. Pull off the jet cover, remove the jet, and measure the distance from the top of the tube to the fuel level. Pull the bowl off again, dump the fuel, and change the float jet height with more or less shims, refit the bowl and turn on the fuel supply… the fuel level in the tube will reflect the shim change.

I had to carefully file off some of the excess solder from old repairs to drop some weight, as you can only space the float valves so far down before you run out of threads. I eventually got both floats happy and the fuel reliably shutting off where I wanted it.

The motor fired easily enough the first time, but it made quite a lot of blue smoke out the tail pipe, which was worrisome. Part way through the first test drive, it fouled the spark plugs and stopped running. We changed to plugs with a heat range 2 stages hotter (from 7 to 5 on the NGK scale) and it would run without fouling, but was still running badly. It would not accept throttle without bogging and would backfire regularly. Based on how wet and sooty the plugs were, I took an initial guess that it wanted less fuel and we changed the main jets from 125 to 115 (solder the jet and re-drill).

That was not a winner, so we went straight the other way to 135, and suddenly it came alive. I adjusted the distributor hand control to max out at 50°, and it liked the increase in advance, revving more freely still. Now it ran well enough that the plug choice may have been too hot, with the insulators looking extremely clean and almost white. We went colder to a set of sixes, and increased the main jets again to 145, which was better still. Now being freely revved on the test drives, I suspect the gummy piston rings freed up and it no longer smoked.

A minor change that improved the idle quality and the throttle response was to remove the fiber washers that a previous mechanic had added under the idle jets. The idle fuel supply comes through the idle jet, and there is an air gap around where it meets the carb body that draws air into the fuel to help emulsify it. The washer was obscuring the air gap and making the mixture much too rich. The previous guy had also inserted a washer in the main jet holder that I suspect was preventing the jet from seating fully and allowing excess fuel to bypass the jet, making it richer still, which is why it lived at all with such small main jets .

Happy with where it was, I packed up to go spend a week with a different Bugatti in Southern California.

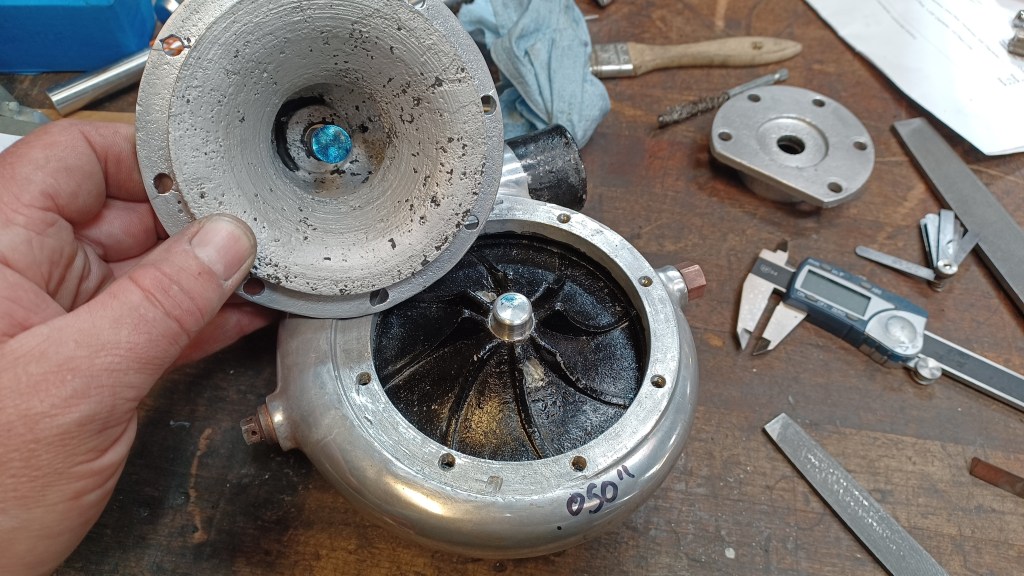

When I got back though, the car was partially apart, as the water pump hadn’t liked the sudden increase in activity and was pouring out water. It was supposed to leave in a couple of days and there was no time to order new parts, which often in the Bugatti world, arrive as unfinished castings that need much machining.

We determined the best route to getting the car to the event was to make a new shaft and otherwise tuneup the parts we had. And they needed it! The shaft bushing was badly worn, as was the shaft, in all sorts of ways. The cast aluminum impeller was expertly removed from the rotten shaft by one of my co-workers while I was away, and though the threads were quite bad, there was enough to work with.

So I machined the basic shape of the new shaft from a billet of steel, making it oversize to fit the original bushing that I had reamed to remove the taper wear at each end. The tricky bit was to make the odd-size Bugatti thread for the impeller in a way that it fit securely. I had single-pointed a couple of test pieces to find the best thread major diameter, which was a fair bit larger than the calculated ideal. The female thread in the impeller was worn in a taper though, so further hand work on the new shaft was required to get the impeller seated solidly onto the shoulder of the shaft.

A little tuneup was needed on the end-float button, which was seized in the very fragile looking cover, having been previously welded up somewhere back in time. I didn’t want to break it trying to get it out, and was able to get it in the lathe well enough to face it flat. Then I shortened the new shaft to set the end float, accompanied by a paper gasket of the right thickness. The gland nut that holds the pump packing got tuned up and the bore enlarged to suit the new shaft.

Finally, the square drive dog that transmits rotation from the engine’s cross shaft to the pump needed the heavily worn squares welded up and filed to shape. Some of the castings were corroded under the water hoses, and those got sealed with a ceramic epoxy coating that’s worked for us in the past.

These repairs were not the ideal solution, but were enough to get the car through its debut event. A better repair would have included a new cover casting with a new end float button, new impeller casting and new shaft, but that was not possible in the time available.

Overall, the car went from being virtually unusable to a pretty nicely driving Bugatti, and it made it through its event with no dramas and a happy owner. It’s the kind of project that delivers a sense of satisfaction and makes me feel good about my work. It doesn’t happen every day!

Leave a comment